Is It Safe to Eat a Bruised Apple? How to Tell When Produce Is Too Far Gone

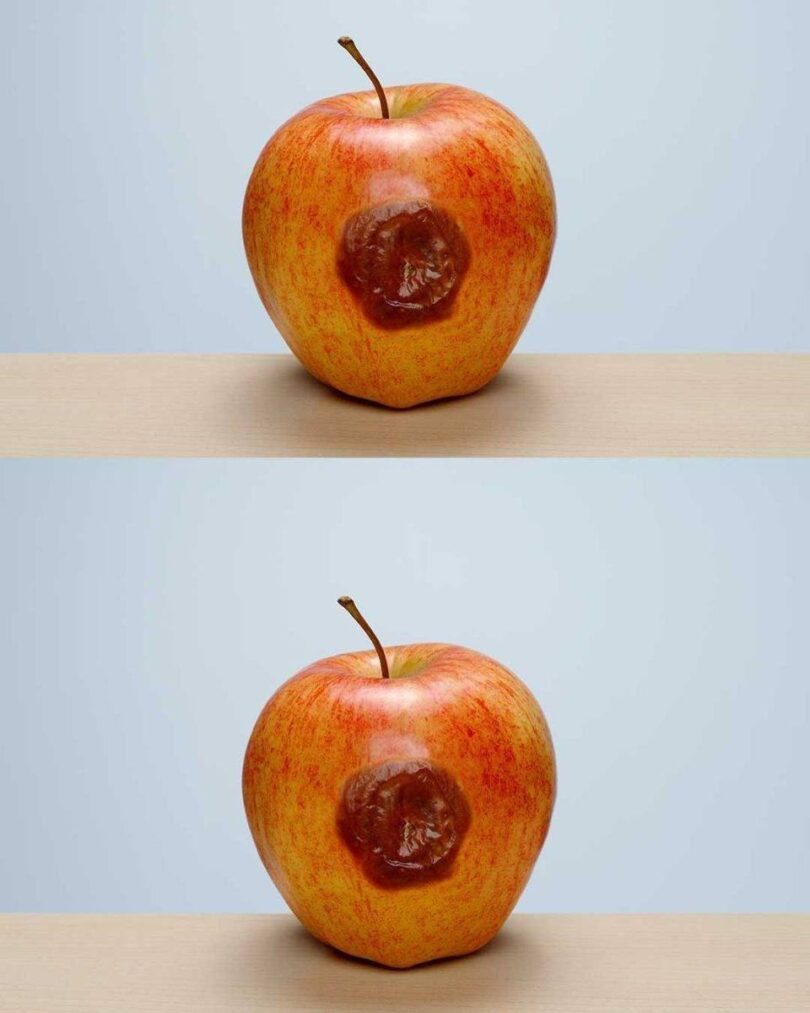

“My mother-in-law will eat an apple when it’s bruised like this. I don’t think it’s safe, but she disagrees.”

If this sounds familiar, you’re not alone. Bruised fruit—especially apples—sits right at the intersection of food safety, thriftiness, and generational wisdom. Some people were raised to cut off the bad part and eat the rest. Others were taught that any visible damage means “throw it away immediately.”

So who’s right?

The truth is more nuanced than either side usually admits. A bruised apple isn’t automatically unsafe—but it can become unsafe depending on what kind of damage it has, how old it is, and what else is going on beneath the skin.

Let’s break down what bruising really means, when it’s harmless, when it’s risky, and how to make a clear, confident call without turning it into a family argument.

What Is a Bruise in an Apple, Really?

When you see a brown or soft spot on an apple, you’re usually looking at cell damage, not decay.

Apples bruise when they’re dropped, squeezed, or bumped during harvesting, transport, or storage. The impact breaks cell walls inside the fruit. Once that happens:

Oxygen reacts with enzymes in the apple

The flesh turns brown (similar to a cut apple)

The texture becomes softer or mealy

This type of browning is called enzymatic oxidation. On its own, it’s not dangerous. It’s a quality issue, not a safety issue.

So yes—a simple bruise does not automatically make an apple unsafe to eat.

That’s the part your mother-in-law is probably right about.

But that’s not the whole story.

When Bruising Becomes a Problem

Bruising creates weakened tissue, and weakened tissue is more vulnerable to things you don’t want to eat—like bacteria, yeast, and mold.

Here’s where the line between “ugly but fine” and “don’t eat that” starts to matter.

1. If the Skin Is Broken

The apple’s skin is its main defense system. Once it’s punctured, torn, or split:

Bacteria from hands, surfaces, or the environment can enter

Microbes can spread beyond what you can see

Cutting off the visible bad spot may not remove the contamination

If a bruise is accompanied by:

A crack

A puncture

A leaking or wet area

…it’s much riskier than a closed bruise under intact skin.

Rule of thumb:

A bruise under intact skin = usually okay.

A bruise with broken skin = treat with caution.

2. If It’s Soft, Mushy, or Spreading

A fresh bruise is usually firm, just discolored.

Red flags include:

The spot feels mushy or slimy

The soft area is growing larger over time

The apple smells fermented, sour, or “off”

This can indicate internal breakdown or early rot, not just bruising. At this stage, microorganisms may already be at work.

If the apple feels like it’s collapsing from the inside, it’s time to let it go.

3. If There’s Mold—Even a Little

This is the clearest “no.”

Mold on apples can appear as:

White, gray, blue, or green fuzzy patches

Dark circular spots with a powdery look

Growth around the stem or inside a crack

Unlike bruising, mold can produce mycotoxins, which may spread invisibly through the fruit. Cutting off the moldy part is not considered safe for firm fruits like apples, because:

Mold roots (hyphae) can extend deep into the flesh

Toxins can remain even where mold isn’t visible

If you see mold anywhere on the apple, the safest move is to discard the whole thing.

The Gray Area: “Just Cut Around It”

This is where most disagreements happen.

For firm fruits like apples, food safety experts generally agree:

You can cut away a bruise if:

The skin is intact

There is no mold

The flesh smells normal

You remove at least ½–1 inch around the damaged area

After trimming, the remaining apple should be:

Firm

Fresh-smelling

Normal in color and texture

If you’re cooking the apple (baking, stewing, making applesauce), trimming bruises is even more acceptable because heat reduces microbial risk—though it won’t neutralize mold toxins if mold is present.

Leave a Comment